1540-1858 | 1844-1866 | 1866-1877 | 1877-1900 | 1900-1919 | 1919-1941 | Introduction

A number of standard gauge railroads were important to Fort Collins in providing transportation access and opening up markets to the community. The arrival of the railroads ended the isolation of the community and made possible the importation of manufactured building materials from the East. The first railroad to reach Fort Collins was the Colorado Central in 1877, followed by the Greeley, Salt Lake, and Pacific (GSL&P) in 1882. These lines, both subsidiaries of the Union Pacific (UP), were later consolidated into the Colorado and Southern Railway in 1898 following reorganization of UP holdings. In 1910, the Union Pacific prepared to lay track into the city and, in clearing its right or way, destroyed sizable numbers of the city's most historic structures along Jefferson Avenue, including many historic residences.

The Arrival and Development of Railroads

The Colorado Central Railroad was organized by W.A.H. Loveland of Golden and others in 1865 as the Colorado and Clear Creek Railroad Company. The objectives of the company were to build lines from Golden up Clear Creek Canyon to mining areas and to connect with Boulder and other points to the north. The line was supported by the Union Pacific Railroad with financial backing and donated equipment. In the early 1870s, the Colorado Central built a line northward from Golden to Boulder and then northeast to Longmont, which was reached in 1873. The Panic of 1873 halted construction on a planned extension from Longmont to Greeley. When construction resumed in 1877, the railroad decided to build directly north to a connection with the UP mainline near Hazard, Wyoming, just west of Cheyenne. This linkage would give the "UP access to Colorado trade independent of the KP [Kansas Pacific] or DP [Denver Pacific]."

Fort Collins was the main population center along the proposed alignment of the Wyoming extension of the Colorado Central. In order to ensure that the town was not bypassed by the Colorado Central, the Fort Collins Board of Trustees enacted an ordinance in June 1877 giving the railroad a right of way north-south through the town along Mason Street, plus additional land for yards and a depot. Of the alignment cutting through the town, railroad historian Kenneth Jessen opined that "Fort Collins would ultimately live to regret this decision as rail traffic grew and trains became longer."

Inadequate transportation had hindered the growth of the Fort Collins area, with wagon roads to Denver and Cheyenne so poor that they were passable only during good weather. Jessen noted that the foothill area in Larimer County was ideal for wheat-growing (as evidenced by local milling activities), but "shipping the flour to outside markets was prohibitively expensive" given poor transportation facilities. While the mid-1870s had seen development stagnate within Fort Collins, the coming of the railroad in 1877 was an impetus for a surge of growth.

Building south from Wyoming, the rails reached Fort Collins in September 1877 and the segment to Longmont was completed by November of the same year. The communities of Loveland and Berthoud would soon develop along the stretch of track between Fort Collins and Longmont. Watrous eloquently describes the impact of the rail link on Fort Collins:

The advent of the railroad marked the beginning of a new era in the history of Fort Collins and Larimer County. It opened communication by rail with the outside world and brought the town in touch with the rest of creation. It afforded the farmer and stockman an opportunity to ship out their surplus products and fat cattle to wider and better markets. The home merchants could also get in their stocks of goods in better time, in better condition and at a cheaper rate, consequently the producers and consumers were all benefitted.

By the spring of 1878, Fort Collins was in the midst of a new period of prosperity and development, during which a number of the city's most substantial business blocks, public buildings, and residences would be erected. An influx of new settlers from the Midwest took advantage of rail transportation to bring families, household goods, farm implements, and farm animals directly to the area. The railroads actively encouraged immigration by advertising the region in order to sell their land grant acres and by offering special rates for emigrant cars in which farmers could transport their belongings. The town, whose economy depended upon the success of the agricultural sector, prospered as a supply center for the new emigrants.

The second railroad to reach Fort Collins was the Greeley, Salt Lake, and Pacific Railroad (GSL&P), a line under the control of the Union Pacific. The GSL&P was incorporated in January 1881 in response to surveying activities up the Cache la Poudre Canyon by the Denver, Salt Lake, and Western Railroad, a line associated with UP's rival, the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy. The UP conducted its own surveys in the canyon and, by February 1881, had construction teams working in the area. The quick action by the UP apparently dissuaded the rival line from pursuing its plans for tracks up the Cache la Poudre Canyon.

As initially proposed, the GSL&P was intended to run from Greeley to Fort Collins and westward to Salt Lake City, Utah. To aid in the line's construction, the railroad requested that Fort Collins provide a free right of way through the town. A town meeting was held on the question in July 1881 and the town Board of Trustees acceded to the request, tempted by visions of Fort Collins on a transcontinental rail route. Jessen observed that the town "had illusions of much more than the GSL&P was ever to provide."

The GSL&P located a right of way on the northern fringe of town, roughly aligned with Willow Street on a slight northwest-southeast orientation. The cost of compensating affected property owners was seven thousand dollars and in only a few cases was outright condemnation employed. The initial tracklaying on the GSL&P in October 1881 was a 15.4 mile branch from Fort Collins to Bellvue and then south to an area of stone quarries that had developed along the hogback west and south of Fort Collins. In December 1881, the first thirty-five carloads of high quality sandstone, hauled by wagon from the quarries, was shipped from Laporte. By May 1882, the branch line had reached the southern end of Horsetooth Valley, and, by June 1882, up to four trains a day were running from the Stout quarries. The 24.5 miles of connecting track between Greeley and Fort Collins were laid between May and October 1882, and the first GSL&P train rolled into Fort Collins over the link on 9 October 1882. Fort Collins was not destined to be part of a transcontinental route. In the fall of 1882 the Union Pacific determined that the effort to push a line through the Cache la Poudre Canyon was too expensive and abandoned the project.

A number of changes in railroad operations and trackage occurred as a result of the Colorado Central and the GSL&P both being under control of the Union Pacific (UP). In 1883, service on Colorado Central trackage north of Fort Collins was discontinued, with traffic diverted to the GSL&P route to Greeley and thence north to Cheyenne. The stated rationale was the poor condition and more difficult grades of the older Colorado Central route north to Wyoming. More cars could be moved by a single engine over the GSL&P route versus the older Fort Collins-Hazard alignment. The abandonment of the tracks north of Fort Collins left the small communities of Bristol and Taylors without rail service. While this loss of market access sparked protests and lawsuits in Fort Collins, tracks were physically removed in 1890.

The agricultural sector was a major customer for railroads in the region, but the late 1880s were a difficult period for cattle ranchers. During the part of the decade, businesses overexpanded and subsequently, a period of stagnation set in. Farmers, who had gone into debt to acquire land, experienced a lack of demand for alfalfa and a decline in value of cattle and horses. A harsh winter during 1886-1887 was referred to as "the big die-up" as cattlemen lost as much as half their herds. Fortunately, in 1889, a new agricultural activity was initiated, which would become one of the foundations of the farming economy in the Fort Collins area. In that year, a blizzard halted the railroads, delaying at Walsenburg a shipment of New Mexican lambs received by E.J. and I.W. Bennett and headed for Nebraska. When transportation reopened, the lambs were in too poor a condition to be sent east. Instead, they were sent to Fort Collins, where alfalfa hay was plentiful. The lambs were fattened on hay and corn by Charles F. Blunck for the Bennetts. In 1890, the fattened lambs were marketed in Chicago, where they produced a profit. This was the beginning of a major industry for the Fort Collins area. In 1889, 3,500 lambs were fed, and by 1901, 400,000 were being fed. Major lamb feeders during the early twentieth century included W.A. Drake, Peter Anderson, Blunck, Jesse Harris, and the Zieglers.

The farmers in the vicinity of Fort Collins joined together in an effort to improve their livelihood in 1884 through the organization of the Farmers Protective Association. The group incorporated with the object of building mills and elevators, buying and selling real estate, and manufacturing flour. The organizers hoped to protect the interests of local wheat growers against millers' discrimination in the purchase of grain. Leaders of the group included John G. Coy, Peter Anderson, Joseph Murray, and J.E. and Z.C. Plummer. The farmers built Harmony Mill in 1884, a portion of which is still standing (See Figure 14). The mill had the capacity to process six hundred one-hundred-pound sacks of flour a day. The Harmony Mill quickly ran into problems through mismanagement and by 1901, the mill was closed and in litigation with creditors. In 1906, the Sanborn Map describes the building as a "vacant old mill."

In 1890, the Union Pacific formed a new subsidiary, the Union Pacific, Denver, and Gulf Railroad (UPD&G), which consolidated the Colorado Central, Greeley, Salt Lake, and Pacific, and other lines extending southward to Texas. The UPD&G existed for three years until the entire UP system went into receivership. In 1898, the Colorado and Southern Railway was created, including the former trackage of both the Colorado Central and the GSL&P lines.

Colorado State Agricultural College

Three public institutions for higher education were created and built in Colorado during the 1870s: the Colorado School of Mines in Golden (1874); the University of Colorado in Boulder (1877); and the State Agricultural College in Fort Collins (1879). The Colorado territorial legislature determined the locations of these institutions, as a result of various communities vying for the honor of being chosen as the site of such facilities as the state prison, insane asylum, and university. Representatives of Larimer County realized the economic and political advantages of locating a government institution in their community. As James Hansen has noted, the acquisition of a college was considered desirable because it would enhance the city's prestige and insure a "center of culture, an enlarged and refined population, and a variety of economic rewards."

The idea of establishing an agricultural college in Fort Collins was initially advanced by Larimer County Representative Harris Stratton in 1867. In February 1870, Matthew S. Taylor followed up on Stratton's concept and introduced in the territorial legislature an act establishing what he referred to as the "Agricultural College of Colorado" at Fort Collins. Apparently some legislators voted to grant Fort Collins the college in the belief that an agricultural college in "the Great American Desert" was pure fantasy. Trustees were appointed to organize the college and purchase the necessary property, erect buildings, and employ a teaching staff. Unfortunately, no money was appropriated to accomplish these tasks. The first trustees included a number of prominent Colorado citizens, including Samuel H. Elbert, Granville Berkley, Benjamin Whedbee, and Jesse M. Sherwood.

Although no state funding had been forthcoming, residents of Fort Collins were determined to push ahead with the creation of the college. Local settlers and businesses thus donated land for the college campus. In 1871, Robert Dalzell, who had a homestead near the town site, donated thirty acres of land for the institution. In 1872, eighty acres of land were donated by the Larimer County Land Improvement Company, the same development group which had established the Fort Collins Agricultural Colony. Pioneers A. H. Patterson, John Mathews, Joseph Mason, and Henry C. Peterson also donated land for the site.

In 1874, the territorial legislature appropriated one thousand dollars as start-up money for the college after intense lobbying by Norman H. Meldrum. Meldrum was a pioneer farmer and stockraiser, who served as Larimer county assessor, member of the territorial and state legislatures, secretary of state, and lieutenant governor before moving to Wyoming in 1897. The legislature appropriated the money with the stipulation that the college trustees raise a matching amount.

In order to further the probability that the college would actually be built, Fort Collins citizens erected a board fence around a portion of the donated land and constructed a "claim" building designed by local banker A. K. Yount on the donated campus acreage. The small claim building (demolished) was erected at the southwest corner of College and West Laurel. This first building on the college campus was initially utilized for storage and later housed the first college president. Henry Patterson planted trees along the road to the site to further enhance its appearance. In 1875, the local grange evidenced its support of the college when it plowed up twenty acres of the donated campus land and planted it, raising a crop to be sold to establish a fund for the institution. The grain was harvested, threshed, stored in the claim building, and eventually sold to the local mill.

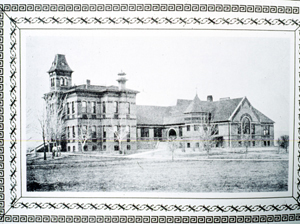

When the state constitution was written in 1876, it incorporated the concept of an agricultural college and a state board of agriculture to oversee it. In 1877, the college took a step nearer to becoming a reality when a state funding act levied an assessment on taxable property in order to secure money for the construction of buildings at the institution. In addition, a State Board of Agriculture was created to govern the college. This support for the college resulted in the formulation of plans for the first classroom building. Combined taxes for 1878 and 1879 netted a construction budget of eight thousand dollars for the construction of "Old Main." When the building was completed in 1879, the college officially opened. Historians Abbott, Leonard, and McComb observed that the "massive new college building expressed the desire to build a cultured commonwealth and affirmed Coloradans' faith in the practical application of learning to railroads, mining, irrigation, and industry."

In the early 1880s, the college's continued existence appeared somewhat uncertain, and Hansen reported that the university at Boulder went so far as to attempt to recruit the agricultural college's students. The students themselves helped advance the prospects of the institution by assisting the campus buildings and grounds crews in completing repairs and improvements. Although the local agricultural economy suffered during the late 1880s and a general economic downturn was experienced in the state in 1893, enrollment at the college (which stood at 146 in 1892) grew after the initial period of uncertainty.

Growth of the City

Although sparse in some cases and interspersed with vacant blocks, many blocks of the original plat of 1873 had begun to experience development by the mid-1880s. Fort Collins sign painter and French immigrant Pierre Dastarac produced a bird's-eye-view map of the Fort Collins in 1884 (See Figure 15). The view created by Dastarac was to the southwest from beyond the northeastern edge of town and included the developed area of the community. Around its edges, the map also included line drawings of the principal commercial and public buildings of the town.

The earliest Sanborn insurance map coverage of Fort Collins, produced in 1886, provides detailed information on existing land uses and building footprints for the most heavily developed area of the city, extending from Willow Street on the northeast to Olive Street on the south and from roughly Howes Street on the west to Lincoln Avenue and Whedbee Street on the east. The map indicates that streets within the city were not paved and shows bridges over the Cache la Poudre River at College and Lincoln Avenues. Railroad tracks of the Greeley, Salt Lake, and Pacific (GSL&P) are shown on a slight northwest-southeast orientation through the town roughly aligned with Willow Street. The Colorado Central Railroad tracks are shown along Mason Street north-south through the town. A freight and passenger depot is shown on Mason Street between Maple Street and Laporte Avenue.

The principal industrial sites of 1886 Fort Collins were found on the northeastern edge of town and in the northern area along railroad lines. The Garbe Brothers Machine Shop and Foundry was located on Riverside Avenue near Smith Street. A two-and-a-half story grain elevator of the Colorado Elevator Company with a capacity of 55,000 bushels was located on the Colorado Central railroad tracks at the northwest corner of Maple and Mason streets. Two water-powered mills of the Colorado Milling and Elevator Company were also shown. The Inter-Ocean Mills were located on the northwest corner of Cherry and Mason streets along the Colorado Central Railroad. The mill was three and a half stories with a two story warehouse. The Lindell Mills were situated on the GSL&P railroad line in the northeastern part of town at the intersection of Willow Street and Lincoln Avenue. The mill was of four stories with a two story warehouse and a 150,000 bushel elevator.

The commercial and business area of the town in 1886 covered approximately forty-three acres and stretched from Jefferson Avenue on the northeast, southwest to the intersection of College Avenue and Mountain Avenue and west to College Avenue and Laporte Avenue. Figure 16 maps the growth of the Fort Collins commercial core between 1886 and 1925, based on an analysis of successive Sanborn fire insurance maps. A number of hotels were found within the 1886 commercial area: the Tedmon House at the northwest corner of Jefferson and Linden; the Collins House on Jefferson between Linden and Chestnut; the Cottage House on Jefferson between Pine and Linden; and the Commercial Hotel at College and Walnut. Jefferson between Pine and Chestnut, Linden between Willow and Mountain, and College between Mountain and Walnut displayed the heaviest concentrations of commercial structures. Groceries, dry goods, restaurants, hardware, drugs, jewelers, laundries, printers, furniture, carriage and harness supplies, saloons, and hotels were among the enterprises found in this area. Most of the buildings in the commercial core were one to two stories in height, with only the Tedmon House, Collins House, the Opera House, and Poudre Valley Bank/Linden Hotel at three stories. Offices were located on floors above street level. This area was by no means exclusively commercial and contained a number of residential units, along commercial blockfaces or on the periphery of such blocks, as well as on upper floors of some businesses.

Public facilities included the town offices on Walnut between Pine and Linden, which also housed firefighting equipment and a bell tower. The Post Office was at the corner of Linden and Mountain. A small "calaboose" was shown on Sanborn maps on the alley between Jefferson and Walnut and Linden and Chestnut. A frame office and stone jail were located on Courthouse Square at Mason and Mountain; the large courthouse had not yet been constructed. Remington School was situated at the southeast corner of Olive and Remington. Only a few buildings of the State Agricultural College are shown, located just southwest of the intersection of Laurel and College: a college building, dormitory, mechanical building, and chemistry laboratory.

A few churches are shown on the 1886 Sanborn map: the Methodist Church near the corner of Mountain and Walnut; the Presbyterian Church at Walnut and Linden; the stone Episcopal Church on the southeast corner of College and Oak; and the frame Catholic church near Mountain and Riverside.

A overview of the physical development of Fort Collins at the end of the century is provided in Merritt D. Houghton's 1899 bird's-eye-view map of city (See Figure 17). Houghton was an artist who later moved to Laramie, Wyoming, and specialized in sketching ranches and the countryside. His 1899 map essentially replicated the view and coverage of Dastarac's 1884 effort. The 1899 map graphically illustrates the densification of the commercial core, with previously vacant or residential areas replaced by larger and generally taller commercial structures. The expansion of the business area onto the south blockface of Mountain Avenue and further north along College Avenue is also evident. The presence of a number of large public structures on the 1899 map, such as the Courthouse, Remington School, and Franklin School, is also a striking difference. Discussing the 1899 map, Swanson observed that "there are many more buildings on the campus. There is a luxuriant growth of trees. Even in the old parts of town many blocks were not yet occupied."

Commercial District Growth

In 1879, forty-one buildings were erected in Fort Collins and Watrous noted that 1,150,000 bricks were laid. As the building boom of the late 1870s expanded during 1880, lots which had been offered for fifty to seventy-five dollars at the end of 1879 sold for five to eight hundred dollars by 1880. The 1880 Census showed the town with 1,356 inhabitants as the twelfth most populous municipality in the state. Table 1 displays population growth trends and rankings for 1880 through 1940. Growth of around fifty percent was recorded during both the 1880s and 1890s, as Fort Collins topped two thousand residents in 1890 and just over three thousand in 1900. Despite the rate of growth, the town dropped to the sixteenth largest in Colorado in 1900 as a result of more rapid growth occurring in booming mining communities.

Hotels

The growth of the town also resulted in an increase in visitors to the city. Hotels were built to accommodate guests and often the enterprises included restaurants and bars which made them a center of social events. D. M. Harris moved the front part of the old Agricultural Hotel to College Avenue near Walnut, enlarged the building, and renamed it the Commercial Hotel. Harris later had the frame building razed and erected a three-story brick building on the lot. The new hotel boasted fifty rooms, electric lighting, steam heat, and a large dining room. The building's proximity to the Colorado Central Railroad station made it a popular stop for travelers and businessmen.

The Tedmon House, built by Bolivar Seward Tedmon, opened on 20 May 1880 and was reputedly the finest hotel in Colorado north of Denver (See Figure 18). Located on the northwest corner of Jefferson and Linden, the Tedmon House contained sixty-five handsomely furnished rooms and was a popular hostelry for thirty years. In 1909, the Tedmon House was sold to the Union Pacific Railroad, which temporarily used it as a depot and then razed it in 1910.

A competitor of the Tedmon, the Linden Hotel was completed in 1883 at the northwest corner of Linden and Walnut. Abner Loomis and Charles Andrews erected the block house the hotel and the Poudre Valley National Bank. The Poudre Valley National Bank had started as a private institution in 1878. Officers of the bank included William C. Stover, president, and Charles H. Sheldon, cashier. The Loomis and Andrews building was designed by William Quayle, a Denver architect who designed a number of buildings in Fort Collins.

Opera House

By the beginning of the 1880s, residents of Fort Collins felt that they had created a cosmopolitan community which favorably compared with other Colorado towns in its possession of the trappings of culture and civilization. An essential ingredient of a sophisticated town during the late nineteenth century was an opera house. Central City erected its opera house in 1878 and Horace Tabor built one in Leadville in 1879. Traveling minstrel and vaudeville companies were available for one night stops and the large, elegant opera houses featured the best entertainment available.

Opera houses were most popular in the more prosperous and developed towns of the state and it seemed fitting that Fort Collins should construct its own structure. With the support of a group of prominent businessmen, including Franklin Avery, Jay H. Bouton, Dr. C.P. Miller, M.F. Thomas, and P.S. Balcam, an opera house for Fort Collins was planned. John F. Colpitts designed and built the three-story opera house block which opened in 1881. Jacob Welch, whose dry goods store had burned earlier in the year, joined the group and a new Welch Block was erected as part of the Opera House Block. The investors thus used the opportunity of erecting a new business block to combine the functions of the opera house, a bank, a retail shop, and a hotel, the Windsor. The First National Bank, of which Franklin C. Avery was president from 1881-1909, was a major occupant of the block. The bank, which incorporated as the Larimer County Bank in 1880, opened for business in the Opera Block in 1881. In 1882, the bank became known as the First National Bank of Fort Collins.

City Services

The frame and brick Welch Building fire in 1880, which cost two lives, motivated the town to establish a Hook and Ladder company during the same year. The unbridled expansion of the business and residential sectors resulted in the need for more formal government offices and fire equipment. In 1881, a combined city hall and fire station building was erected on the north side of Walnut between Pine and Linden. It was common during the period to combine both activities in one building.

In 1882, city services were further expanded when the town approved by vote a city water system for domestic and fire purposes. Previously, residents obtained water from the town water wagon, which was now considered unsanitary and obsolete. The contract for the system went to Russel and Alexander of Colorado Springs. H.P. Handy was engineer in charge of construction. The water was taken from the Cache la Poudre River west of Laporte through an open ditch to the pump house and from there through city mains by pumps driven by water wheels.

In 1887, a company known as the Fort Collins Light, Heat, and Power Company was incorporated by W.B. Stewart, E.P. Roberts, E.T. Dunning, and William B. Miner. The company was organized to build and operate an electrical plant in the city. Stewart was a mechanical engineer from Denver and Roberts was general manager of the electrical system in Cheyenne. The plant at the northwest corner of West Mountain Avenue and Mason Street provided power until 1908 when the franchise was purchased by the Northern Colorado Power Company. At that time, the old power plant was dismantled.

Another convenience for city dwellers was the telephone system installed in 1887. In 1893, the city granted a franchise to the Colorado Telephone Company to build a line connecting Fort Collins with other Colorado cities. In 1909, the Telephone Company erected a building on College Avenue. By the early twentieth century, Fort Collins had adopted many of the services which marked a progressive city.

County Courthouse

Although the harsh winter of 1886-1887 had profound effects on the livestock industry in the West, Fort Collins was somewhat insulated from the devastation felt by other areas because its businessmen held diversified interests. During the year, a number of city improvements and major building projects pushed forward. In 1887, work on the Larimer County Courthouse, designed by architect William Quayle, began in Courthouse quare in New Town between Mountain and Oak Streets. Barney Des Jardines of Fort Collins was the contractor for the building which cost $39,379. Kemoe & Bradley completed the stone work and John G. Lunn subcontracted the brick work on the building.

At the dedication ceremonies for the building, the public was reminded of the heroism of those who had braved the hardships of the frontier to establish homes and local governments. The citizens of the county were asked to view the building as a monument to their commitment to future generations. At last, the county had an appropriate monumental building worthy of its county seat. When the courthouse was demolished in 1957, it reportedly took two days to topple the tower.

Saloons

Although the founders of the city had discouraged the establishment of saloons, in 1875 the ordinance prohibiting the sale of liquor was repealed. Frank C. Miller, a Danish immigrant, miner, and saloon owner operated one of the most successful saloons in town and built the Miller Block. The northern two-thirds of the building was completed in the fall of 1888 at a cost of twenty thousand dollars, and the rest of the building was erected a few years later. W.S. Bernheim established a clothing store in the northern part of the building, the second floor was divided into offices, and Miller had his liquor store in another part of the building. After Miller died, his son, Frank C. Miller, Jr., operated the Fair Store in the building.

By 1883, Watrous noted that "the town was over run with saloons and places where intoxicants could be obtained." These businesses included thirteen bars, three drug stores which sold liquors, five houses of prostitution which sold liquors, and gaming houses. Watrous stated that the "town was full of idle and vicious men, driftwood from railroad and ditch camps, irresponsible creatures, without home or friends, who hung about the saloons and brothels." At that point, liquor licenses cost three hundred dollars.

An election was held, and those favoring a high liquor license won, led by Mayor A.L. Emigh. The liquor license fee was then set at one thousand dollars. This weeded out all but six saloons. "The riff-raff, flotsam and jetsam, the gamblers and many of the loose women that had floated in here during the 'wide open' period, found it convenient to leave the city and seek locations where they could more safely ply their nefarious avocations." In 1896, the city enacted a prohibition law.

Avery Block

In 1897, the Avery Block, one of the city's most significant commercial buildings, was completed near the intersection of College and Mountain avenues. The building, which was composed of three sections on the triangular lot, housed Avery's First National Bank and a number of stores and offices. Avery had been contemplating construction of a new bank building on the site since 1884, apparently dissatisfied with the Opera House location. In 1896, Fort Collins architect Montezuma Fuller revised the drawings for the block produced in 1884 and the building opened the following year (See Figure 19). Lawrence Baume has noted that Franklin Avery considered the intersection of Mountain and College the "hub" of the town's commercial district, as it linked the old and new business areas.

Residential Development

The Fort Collins town plat of 1873 embraced roughly 935 acres of land. As the population of the town increased, residential additions were platted in order to separate industrial, commercial and housing areas. A few large residential subdivisions were created in the city prior to 1900, predating the streetcar era. The first residential subdivisions after the original townsite were platted in 1881. Earliest development activity included the Harrison Addition (1881) and the Lake Park Addition (1881). Other major subdivisions platted before 1900 included the Doty and Rhodes Subdivision (1883), the A.L. Emigh Subdivision (1886), the Loomis Addition (1887), and the West Side Addition (1887). Table 2 presents a listing of pre-1940 subdivisions within the city. At the end of the nineteenth century, Fort Collins covered approximately 1,100 acres.

By the mid-1890s, residential areas within the city had expanded, with principal residential locations to the south and west of downtown with smaller residential areas to the northwest and between Jefferson Street and the river. Dwelling units by block were tabulated from the 1894 W. C. Willits map of Fort Collins and vicinity and are mapped in Figure 20. Only a handful of dwelling units were located west of Whitcomb and north of Cherry. Southeast of the State Agricultural College was a cluster of homes in the Lake Park Addition in an area from Elizabeth to Pitkin and College to Whedbee, which was separated from the main residential area of town by several square blocks of undeveloped land.

An area in the northwestern quadrant of the original townsite which encompasses the eastern part of what is today known as the Holy Family Neighborhood was developed as a working class residential neighborhood. This area, bounded by Whitcomb Street on the west, Mason Street on the east, and Laporte Avenue on the south, and the railroad tracks on the north contained, small, mostly vernacular homes. The presence of the railroad tracks, industrial land uses, and the proximity of the river insured that this area was a less desirable residential sector. The 1894 Willits map indicates that the heaviest development by that date had occurred along Howes Street between Maple and Cherry streets in Block 43. By 1902, Block 42, immediately to the south, was populated by Afro-American residents. Most of the homes in the latter block were removed during construction of the city hall complex. For a further discussion of the Holy Family Neighborhood, see Community Services Collaborative, "Architecture and History of Holy Family Neighborhood," 1983.

The southeast quadrant of the original townsite is what is today known as the Laurel School Neighborhood. One of the earliest of Fort Collins' residential areas, the northwest section of the neighborhood contains many of the older, larger houses in styles such as Italianate, Second Empire, and Queen Anne which were popular during the late nineteenth century. This portion of the neighborhood attracted wealthy businessmen of the city, including Jesse Harris, Jacob Welch, A.W. Scott, and B.F. Hottel. This was the most heavily developed residential portion of the city before 1900. Several churches were built in the area, as well as Remington School. Lincoln Park was located near the center of the southeast quadrant. For a discussion of the Laurel School Neighborhood, see Community Services Collaborative, "Architecture and History of Laurel School Neighborhood," 1983.

The southwest quadrant of the original townsite saw scattered development before 1900. This area also attracted some of the town's pioneer residents, including Franklin C. Avery, Jay H. Bouton, Peter Anderson, and James Vandewark. In 1880, James Harrison purchased forty acres of land one-half mile south of the old section of town. The Harrison Addition, an area extending from Meldrum on the west to College on the east and Mulberry on the north to Laurel on the south, was created in 1881 and developed slowly in subsequent years. In March 1881, J.C. Abbott purchased three lots from Harrison. During the same month, Harrison was reportedly operating a milk route, which he gave up at the end of April. By June, Harrison had returned to Iowa. Development of Harrison's Addition appears to have begun extensively in the late 1880s and continued into the early 1900s.

The addition attracted primarily middle class and working class residents who built homes in styles popular during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The houses of the 1890s utilized stone, brick, or wood, and incorporated popular architectural details such as decorative shingles, spindlework, ornamental brackets, turned porch supports, and segmental window arches. Many of the homes erected during the late nineteenth century were vernacular in design, with minimal exterior ornamentation. The houses built during the early twentieth century reflected the continued popularity of wood shingles and included more classical details, such as porch columns, pilasters, and floral ornaments. Architectural styles found in the neighborhood include Edwardian Vernacular, Foursquare, Classic Cottage, and Eclectic.

In 1881, Abraham L. Emigh platted the Lake Park Addition, a huge area east of College Avenue between Elizabeth and Pitkin. Emigh, a Pennsylvania native and Civil War veteran, came to Fort Collins in 1874. In civic affairs, Emigh served as mayor of Fort Collins, president of the State Board of Agriculture, and state superintendent of irrigation. A prominent businessman, Emigh was the first president of the Larimer County Ditch Company and director of the First National Bank. The addition was some distance from the original townsite, lying east of the college and south of Elizabeth Street and did not see immediate development.

The Doty and Rhodes Subdivision was surveyed in 1881 and the plat was filed in 1883. Zina Doty, who signed the plat in New York, was listed as the owner of the subdivision. The addition embraced a large area east of Wood Street between Laporte and Vine. The Willits map of 1894 indicates only one residence in the subdivision by that date. The owner of the property, located on Park Street, is listed as "Jones." A portion of this subdivision was later resubdivided as the Capital Hill Addition.

In 1890, E.M. and K.D. Craft resubdivided the Lake Park Addition and in the early 1920s, L.C. Moore resubdivided the southern half of the subdivision. Craft's Resubdivision was described as "the poor man's friend," because lots could be bought on installment at low interest rates. Evadene Swanson reported that one of the Crafts was an editor of the Fort Collins Express who soon sold out and moved to California. A map of the city produced by W.C. Willits in 1894 identifies approximately twenty dwellings in the addition in that year, including the homes owned by prominent members of the Fort Collins community such as C. Garbe (on Elizabeth), M.H. Akin (on Remington), T.B. Ogilvie (on Garfield), J.A. Richards (on Remington), and L.J. Hilton (on Garfield). Watrous reported that Akin lived in "a beautiful home at 1008 Remington Street." After the Crafts left, Akin obtained almost a full block of land where he developed a farm within the city. Akin raised horses, cows, chickens, lambs, and started an orchard north of his 1890 stone dwelling. The Shadeland Place ranch of Charles B. Andrews was located just to the east of the subdivision, where Andrews raised imported Shetland ponies. This land later became the site of the Experiment Station farm.

The Loomis Addition of 1887, was a large area on the west side of town bounded by Laporte, Whitcomb, Mulberry, and Washington, platted by Abner Loomis and Malinda Maxwell. Abner Loomis came to the city in 1860 and the Fort Collins Express called Loomis an "energetic factor in building up the country and [one who] has always been identified with the growth and progress of Fort Collins." Loomis, who prospected, freighted, farmed, and established a cattle ranch during the 1860s, was a contemporary of Antoine Janis. In 1894, Loomis became president of the Poudre Valley Bank. He also served as county commissioner and on the town board of trustees. In 1896, Loomis married Mrs. M. Maxwell. The Fort Collins Irrigation Canal curved through the east-central portion of the addition. To promote interest in the development, a house built by Loomis at 121 North Grant was raffled, with anyone purchasing lots in the addition eligible to win (See Figure 21). J. M. Fillebrown of Geneva, Nebraska, won the house in a drawing held 11 May 1888 and sold it a few months later to A.H. Patterson. The Willits map of 1894 indicates that about fifteen houses had been built in the addition by that date, mostly on the northern and eastern edges. The same map indicates that Loomis and Maxwell owned substantial undeveloped acreage to the west of their addition.

In 1887, pioneer businesspersons Franklin C. Avery and Ella B. Yount created the West Side Addition, bounded by Elm, Whitcomb, Laporte, and Wood. Avery helped lay out the streets of the colony town and was involved in a variety of successful businesses, including ranching, real estate, and banking. Ella Yount had established a pioneer mercantile business in the Big Thompson Valley with her husband and operated the first successful bank in town, which opened in 1874. The Willits map of 1894 does not indicate any dwellings in the West Side Addition. The Fort Collins Irrigation Canal is shown traversing the area from the southeastern corner of the addition in a northwesterly direction toward the corner of Cherry and Wood streets.

Architects Active in Fort Collins During the Nineteenth Century and Early Twentieth Century

One of the first architect designed buildings in Fort Collins was the first major building on the Colorado Agricultural College campus, Old Main. George E. King was chosen by the board of trustees of the college to design Old Main based upon plans suggested by other state agricultural colleges. King designed a building in the French Second Empire style, which was popular following the Civil War in the United States. King was a Boulder architect who had designed at least three Second Empire style buildings in Leadville: a private residence, the county courthouse, and a hotel for Horace Tabor.

Harlan Thomas, who designed Judge Jay Bouton's home at 113 N. Sherwood, attended college in Fort Collins in the 1880s. He later left the city to establish an architectural practice in the Denver suburb of Montclair, where he also served three terms as mayor. Thomas then moved to Seattle, where he became director of the School of Architecture at the University of Washington. There, Thomas designed the Corner Public Market Building, which is part of the Pike Place National Historic District.

Denver architect William Quayle was one of the most popular architects in Fort Collins during the early 1880s. Quayle moved to Denver from Illinois in 1880. Quayle's firm designed more than twenty-five school buildings, in addition to business blocks, churches, and residences. In 1881, he designed the Reed & Dauth Block and the Jefferson Block. Quayle designed the Loomis and Andrews Block (Linden Hotel) in 1882 and Franklin School in 1886. Quayle's buildings were described as "much admired for their massive elegance and harmony of effect, while the elaborations of detail and care bestowed upon every part of the work reflects the utmost credit upon his practice methods." Quayle designed the Pitkin County Courthouse in Aspen, as well as a city hall in the Denver suburb of Highlands in 1890. It was fitting that Quayle was chosen to design one of Fort Collins' most important structures, the Larimer County Courthouse.

Montezuma W. Fuller arrived in Fort Collins in 1880, lived there until his death in 1925, and was the city's first licensed architect. Fuller was a native of Nova Scotia, where he worked as a ship carpenter. His first recorded work in Fort Collins was the remodeling of a barn on the college campus into a lab and scientific classroom in 1883. In the same year, Fuller enrolled as a special student at the college. By 1890, Fuller had established a successful practice and was hired by banker Charles Andrews to design his $10,000 stone residence at 202 Remington. During the depressed economic period following 1893, Fuller designed many small cottages in and around Fort Collins. In 1897, he created the Avery Block for prominent businessman Franklin C. Avery. Fuller's workload steadily grew during the early twentieth century and included buildings such as Fort Collins High School (1903), the C. R. Welch Block (1901-1902), Laurel Street School (1906), Laporte Avenue School (1907), C. C. Forrester Block (1907), the YMCA. building (1907-08), and Odd Fellows Hall (1906-1908). Fuller worked on buildings in a number of towns in Colorado, concentrating on Larimer and Weld County structures and including schools, churches, and private residences.

Arthur Garbutt settled in Fort Collins in the early 1900s and was a drafting teacher at the college. Garbutt was associated with Fort Collins builder C.J. Loveland in 1902, and during the early 1900s worked on a number of commercial blocks, residences, and public buildings. In 1905, he designed the Colorado Block, which was hailed as the most modern business block in town at that date and influenced future building in the downtown area. Garbutt assisted Fuller with the drawings for the YMCA building and worked on some private residences. In about 1912, Garbutt left Fort Collins to practice architecture in Wyoming, where he designed a number of buildings in Casper.

Property Types

Context

The Railroad Era, Colorado Agricultural College, and the Growth of the City, 1877-1900. This context includes the period from the arrival of the Colorado Central Railroad in Fort Collins in 1877 to the beginning of the twentieth century.

Potential Property Types

Property types associated with this theme could include railroad associated buildings and structures such as tracks, passenger and freight depots, bridges, water towers, and coal sheds. In addition, residential dwellings and farms are a major property type. Other property types could include college buildings, such as classroom buildings and dormitories, and campus grounds. Businesses could encompass banks, grocery stores, general stores, jewelry stores, hardware stores, laundries, printers, saloons, hotels, the opera house, restaurants, bakeries, offices and service shops. Other resources could include government buildings, such as city hall, fire department, post office, jail and county courthouse. Resources related to utilities could include buildings such as water system structures and pump house, telephone company buildings, sewer systems, and power plants. Other resources could include churches; industrial enterprises, such as mills and grain elevators, foundries, creameries, and packing plants; meeting places, such as fraternal lodges; streets; and park systems and cemeteries.

Residences. By 1879, Fort Collins was reaping sizable advantages from its rail connection. Business was experiencing an upswing and many entrepreneurs were planning the erection of larger, more substantial and ornate commercial blocks. A number of local citizens had become wealthy from their early investment in the town and were ready to show the world that Fort Collins had its own group of successful capitalists. As Denver's power elite built impressive mansions in fashionable neighborhoods, so too, did the power elite of Fort Collins build noteworthy homes. These businessmen utilized local building materials and railroad transported architectural supplies to erect homes entirely different from those of the frontier period.

When the railroad arrived in 1877, Fort Collins suddenly had access to the eastern markets and the architectural ornament and building materials available there. From the plain vernacular designs of the territorial period, the community soon turned to the more complex, formal styles which had been developed by architects in the East. The Victorian styles, which had evolved over many years in the East, were brought westward by architects and builders seeking to profit from the building boom on the frontier and by the new mail-order pattern books.

Suddenly, the new home owner had a choice of styles from which to select in determining the architecture of his residence. Although most of the homes built in the early days in the West were less elaborate examples of styles developed in the East, western citizens were eager to follow newly developed architectural fashions of the nineteenth century. The citizen who could afford to hire an architect could make a personal statement about his lifestyle and status within the community through the style of his home.

The development of steam power in the 1870s led to the production of faster, less expensive machinery which produced a wide variety of architectural ornament, including shingles and moldings which could be liberally applied to building exteriors. Architectural supply companies produced catalogs from which the builder could order any variety of details, as well as entire portions of buildings, such as porches. This, in turn, led to the popularity of elaborate ornament on house exteriors, an essential element of the Queen Anne style. Soon even the simplest homes of the period included wood shingle decoration.

By the late 1870s, most of the exterior ornament on buildings had been factory produced, shipped by rail, and then nailed or glued into place by a builder. Gwendolyn Wright has noted that "the new industrialism did encourage extravagance, even garish display because it made abundant ornament accessible to builders and home owners of all classes." During the same period, the production of glass became less expensive and it, too, could be ordered in varied sizes and forms, including stained, beveled, and leaded.

During the 1880s, the latest building technologies and architectural styles were spread by architect and builder's journals which described detailed methods of construction and discussed the latest building trends. The history and practice of architecture were thus made accessible to the average person and popular interest in the subject was stimulated and at the same time shaped.

Among the earliest formal architectural styles to take root in a fledgling community were Greek Revival and Gothic Revival styles. Greek Revival style, of which few examples are extant in Colorado, was developed in the East in the 1820s, was very popular throughout the nation during the first half of the century, and was utilized in Colorado as late as the mid-1870s. Archaeological discoveries of the era caught the imaginations of Americans who found a new appreciation of the beauty of classical art, literature, and architecture. The democratic ideals being fought for in the Greek War of Independence also brought the civilization to the forefront of American national interest.

The Greek Revival style in Colorado is generally found only on very early buildings and is generally a very scaled down, less pure version of the style. The basic model for the design was the Greek temple with a series of columns supporting an entablature or a triangular pediment. According to Sarah Pearce, characteristic elements of the style as transferred to the Colorado Territory were pedimented lintels over doors and windows, pilaster boards at building corners, transoms and sidelights surrounding doors, and slim, Doric columns.

During the 1840s, European-inspired Romanticism took hold as a reaction to the complexity of modern urban life. One of the most influential architects of the mid-1800s was Andrew Jackson Downing, who authored widely-dispersed pattern books for builders. Downing's philosophy stressed that the design of homes should fit their setting and that the function of domestic buildings should also be reflected in their design. Downing's concept of the house as a domestic symbol included architectural elements such as overhanging roofs with high gables and deep eaves, large entry porches, and delicate ornaments such as brackets and tracery. Downing popularized both the Gothic Revival and Italianate style through his pattern books.

The Gothic Revival style began in England and harkened back to Medieval period castles and churches. Alexander Jackson Davis designed the first Gothic Revival residence in the United States in 1832. Andrew Jackson Downing spread the style through his pattern books and public speaking. The style was popular in Colorado during the territorial period, and often details were found on vernacular residences. The most commonly adapted feature of the style was the tall, steeply pitched gabled roof. The most characteristic detail is the pointed arch window.

The Gothic Revival style dwelling found in Colorado towns was generally identifiable by its steeply pitched roof, clapboard or stone siding, and picturesque composition. Other details might include dripstones over windows, polychromatic composition, decorative vergeboards, pierced aprons, and bay windows. One-story porches commonly had flattened arches or side brackets that mimicked such arches.

The Avery House incorporates elements of the Gothic Revival style and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (See Figure 22). The house was constructed by Franklin and Sarah Avery at the corner of Mountain Avenue and Meldrum Street in 1879. Avery was a New York native who, as a member of the Union Colony, helped lay out the streets of Greeley. In 1872, he was employed as the company surveyor for the Larimer County Land Improvement Company, in which capacity he helped plat Fort Collins townsite. Avery also surveyed irrigation systems, including the one owned by the Larimer County Ditch Company, in which he was active. Avery purchased several lots in the new town and became street supervisor in order to make certain that the streets were properly developed. In this capacity, he transported trees from the foothills to the city and issued precise instructions regarding the planting of trees along the newly created avenues.

The Avery dwelling, which has been called "one of the best examples of the Victorian period" was a two-story sandstone building with multiple gabled dormers and a turret which form a picturesque and eclectic composition. In its construction, Avery spared no expense. The two-story home was composed of Colorado sandstone of two colors. Gothic Revival elements included the rusticated masonry walls and contrasting stone trim; the steeply pitched, flared, roofline; the intersecting gabled bay with flared roofline; and the gabled dormers. The building also reflects the Gothic style in its flattened arch windows. The porch with classical columns was a later addition, as was the tower. Inside the house, luxurious features such as a tiled marble fireplace and ornately carved woodwork reflected the owner's position in the community.

The Italianate style rivaled the Greek Revival and Gothic Revival styles for supremacy in the world of architecture during the decade prior to the Civil War in the East. By the 1860s, the Italianate style had become the most popular in America and had found a place in Colorado Territory. The style had a vertical, often asymmetrical, emphasis and rich ornamentation. Homes constructed in the Italianate style were generally two to three stories in height, and had low pitched, hipped roofs, widely overhanging eaves, and decorative brackets. Large windows, with double-hung sashes and one-over-one lights were common, as were elaborate window surrounds, usually arched or curved. Porches were an important element of the style, and one-story porches with square supports with beveled edges were typical. Elaborate versions of the style featured cupolas or towers, quoins, and balustraded balconies.

The Abner Loomis residence (demolished) was an excellent example of the Italianate style in Fort Collins (See Figure 23). Loomis, a native of New York, had been a prospector in California in 1850 and searched for gold in Colorado with Antoine Janis in the 1860s. Loomis made enough at mining to buy farm land in Pleasant Valley, where he raised food to sell to the mining camps. He entered the cattle business in 1867 and was a prominent businessman, serving as president of the Poudre Valley National Bank and on the board of county commissioners. As befitting such a successful businessman, the Loomis residence at the corner of Remington and Magnolia was one of the largest houses in the city. The two-and-a-half-story Italianate brick residence cost $12,000. Loomis bought the lot for his home in 1880, but did not erect the dwelling until 1885. The house had a truncated, hipped roof and a wide bracketed cornice. A projecting, gabled bay featured a hipped roof dormer with narrow triple windows. Evenly spaced, segmental arched windows dominated the facade of the building. The windows were one-over-one light and had arched hood moulds and shared sill courses. The off-center, one-story porch had a spindlework frieze and balustrade and narrow, squared post supports. The evenly coursed rusticated stone foundation was raised to porch level.

The Josiah McIntyre residence at 137 Mathews is an extant example of the Italianate style. The 1879 brick home was built for a blind Civil War veteran who later became the first blind person to obtain a law degree in Larimer County. The house has a steeply pitched, cross-gabled roof with overhanging eaves, paired segmental arched windows, and a one-story bay window with decorative brackets. Another example of the style is the house at 2912 East Horsetooth Road associated with the farm established by English immigrant Joseph Sainsbury in 1882. Although somewhat altered, the dwelling reflects the Italianate style in its vertical emphasis and low hipped roof with overhanging eaves and wide cornice with decorative brackets.

The Benjamin F. Hottel residence, which was erected at 527 College Avenue, was perhaps the best example of the Italian Villa variation of the Italianate style residence built in the city. Hottel was a successful Fort Collins businessman, owner with Joseph Mason of the Lindell Mills, and later became president of the Fort Collins sugar company and president of the Poudre Valley National Bank. The house was completed in 1882 and was designed and constructed by Richard Burke, a local builder. The two-story house featured a prototypical central tower with mansard roof and stilted arch window. Flanking the tower were two octagonal projecting bays. The house had a hipped roof with overhanging eaves and paired brackets. The central, one-story porch had narrow supports with decorative brackets. The one-over-one light windows were tall, with flat arches and ornamental surrounds. The imposing house survived and continued to be owned by the Hottel family until the 1960s, when it was torn down.

The French Second Empire or Mansard style was also frequently found in Colorado during the Victorian period. The style was very popular for public buildings in the United States during the period immediately following the Civil War, although it was more popular in cities than rural areas and in the Northeast and Midwest than the South and West. The style was called Second Empire in honor of the era of Napoleon III. The characteristic element of the style, the mansard roof, consisted of a steep lower slope and a gently angled top portion. Other elements of the composition could include a projecting bay or tower extending above the roofline, and windows with pedimented or moulded hood surrounds. Other representative details included bracketed cornices and roof cresting. Old Main, constructed at the State Agricultural College in 1879, and the Larimer County Courthouse, both gone, were the best examples of this style constructed in Fort Collins. The architect of Old Main, George E. King, designed several buildings in this style, including a house, hotel, and courthouse in Leadville. William Quayle, the architect of the courthouse also designed other buildings in the style in different parts of the state.

The W. C. Dilts house at 514 Remington is a rare example of the Second Empire style in Fort Collins. The 1889 dwelling has a mansard roof with gabled dormers, eave brackets, a corbelled brick cornice, and windows with decorative crowns. Dilts, who lived in the house for twenty-five years, was co-owner of a limestone quarry.

American architects during the late nineteenth century, inspired by the nation's centennial, were obsessed with finding an American style and looked everywhere for a model. The work of English architect Richard Norman Shaw was discovered and popularized. Shaw specialized in a style that supposedly was based on construction during the eighteenth century reign of Queen Anne. Shaw's work was seized upon by American architects as a source of inspiration for a new style. Noted American architect Henry Hobson Richardson designed the first Queen Anne style house in America in Rhode Island. The architectural pattern books of the day popularized the style, which was widely utilized from the 1880s through the first decade of the twentieth century.

The Queen Anne style emphasized ornamentation through a variety of shapes, patterns, and building materials, made accessible to the public due to advances in technology and transportation. Queen Anne houses had vertical lines with steep gables and angles to catch the light. "Towers and bays projected, verandas and niches receded, chimneys surged skyward." The style favored a variety of building materials for a single building, including brick, stone, wood, stucco, tile, shingles, and stained glass. The newly invented turning lathe ensured that turned porch supports and spindlework would be a significant element of the style.

The Queen Anne style was immensely popular as it could be adapted to any size home, and any lot, rural or urban. Queen Anne could be had by the common man, who might not decorate his home with stained glass, but could afford decorative shingles or a turned spindle support on the porch. Since large plate glass panels were inexpensive and available, colored glass was often limited to small panes bordering large expanses of clear glass.

The Robert Andrews house at 324 East Oak is one of the city's best examples of the Queen Anne style (See Figure 24). The circa 1892 dwelling has a rusticated, sandstone foundation and brick walls, and decorative wooden shingles in multiple gable ends. The house has a decorative cornice, vergeboard with sawn appliques, and a molded sun decoration. A porch on the southern elevation is elaborately decorated with turned cannonball supports, spandrels with open latticework, spoolwork, and a pierced porch curtain. Windows have semi-circular arches and include leaded and stained glass. A door has the ubiquitous panel of clear glass edged with smaller panes of colored glass. The Andrews house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Montezuma Fuller, the city's best known architect, designed his home at 226 West Magnolia to take full advantage of the visual display offered by the Queen Anne style. The dwelling, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, was designed by Fuller in 1890 and built in 1894-1895, reflecting the fact that Fuller survived the economic depression of the 1890s better than a number of architects in the state. The building had a picturesque, asymmetrical design, with varied height gables with decorative shingles and vergeboards, a pierced gable apron, and an ornate porch with spindlework balustrade, chamfered post supports, and curved brackets. Windows represent a full array of available glass during the period as combined on Queen Anne homes, including clear glass, leaded glass, and a clear pane surrounded by small colored glass panes.

The Baker house at 304 East Mulberry is a 1896 Queen Anne House, reflecting the later adaptations of the style. The brick dwelling is two-and-a-half stories, irregularly shaped, with triple front gables with return, and a two-story rounded bay. The steeply pitched gables have varied, decorative wood shingles in the gable ends. The composition of the building includes a raised sandstone foundation, brick walls, and wooden gable ends. A one-story, rounded, wrap-around porch has walls composed of brick and stone and a spindlework frieze. Multiple porch supports are narrow, with brackets. Windows on the first floor have sandstone sills and lintels. This house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Maxwell house at 2340 West Mulberry Street is reflective of a large segment of the homes constructed at the turn of the century, representing Queen Anne ornament applied to more vernacular homes built by the middle class (See Figure 25). The one-and-a-half story brick house confines its ornament to gable ends, a small porch, and window treatment. The porch has a typical Queen Anne frieze and dainty, turned spindle supports. The large parlor window was emphasized with a segmental arch and radiating voussoirs. The dwelling was built by farmer Robert G. Maxwell, and reflects the influence of popular styles on what was, at the time of its construction, a rural area. This house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Boston architect William Ralph Emerson designed the first fully developed Shingle style home in Maine in 1879. Shingle style homes were first constructed in New England as seaside resort homes. As James Massey and Shirley Maxwell note, they were "mansion-sized cottages for the wealthy." The Shingle style was characterized by its horizontal emphasis, with its shingled walls and roof forming smooth planes. Colonial Revival details decorated the exterior, including Palladian windows, oval windows, and small pane sash windows. Such houses had prominent porches and verandas and usually had stone foundations. The style was a contemporary of the Queen Anne, but not as versatile and was much less frequently utilized.

The Shingle style was not widely built in Fort Collins. Local architect Harlan Thomas designed Judge Jay H. Bouton's 1895 residence at 113 N. Sherwood with elements of the Shingle style (See Figure 26). John C. Davis built the house which cost six thousand dollars. Bouton had served as city attorney, alderman and president of the school board and the house reflected Bouton's prominence within the community. The large, hipped roof, two-and-a-half-story dwelling had pedimented, paired, symmetrical cross gables with Palladian motif windows in the upper gable ends, and multi-level eaves. The house had shingled upper walls and clapboard first story walls atop a rusticated stone foundation. The wrap-around porch featured classical column supports, a wooden balustrade, and a pediment shape with decorative medallion over the entrance. Above the porch was a small, inset balcony supported by short columns. The large windows were simple sash and transom and one-over-one light. This house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Although the popular national styles had great impact on Fort Collins, many homes continued to be built in a vernacular manner, with "an absence of architectural features and ornamentation that can distinguish a specific style." Vernacular homes are classified by the Colorado Historical Society according to floor plan and roof shape, including Gabled L, Front Gabled, Hipped Box, and Side Gable. In 1896, Alin H. and Amanda Fry built a very representative one-story frame house with a vernacular Gabled L plan at 202 West Myrtle (See Figure 27). The small dwelling had horizontal board siding with corner boards, a stone foundation, and brick chimney. A porch located at the intersection of the gables was supported by slender, squared, chamfered columns. The home had a sash and transom parlor window (somewhat luxurious for a vernacular house) and one-over-one light double-hung windows with wooden surrounds. Alin Fry was employed in the Horticulture Department of the college for thirty-three years and was a member of the volunteer fire department. Amanda Fry was a skilled seamstress and dress designer who counted the city's affluent matrons as her customers.

Railroad Buildings and Structures. Train depots were "a place of glamour and excitement." The depot was the town's link to the outside world and was thus a focus of town life. The Colorado Central built a small, brick depot in Fort Collins along Mason Street between Maple and Laporte. The 1877 building, which was razed in 1906, contained an office, passenger waiting room, and freight room and was described by Jessen as "typical" of Colorado Central depot construction. Small depots were typically rectangular, one-story buildings with widely overhanging eaves which offered shelter from the elements for waiting passengers. The Fort Collins depot was brick, with segmental arched openings.

The Colorado and Southern (C&S) constructed a new stone depot in Fort Collins that it occupied in January 1899 (See Figure 28). The new station, on Mason at Laporte, reflected Romanesque influences, including its gray stone walls laid in broken ashlar pattern, with cut stone caps and sills and arches. The building had an off-center, two-story tower and a large entryway with stone voussoirs. The building was razed during the early 1950s.

Government Buildings. In 1880, the city built a combined city hall and fire station (See Figure 29). The brick building had a bell tower and an elaborate cast iron cornice with roof cresting. The entrance to the city hall offices had a semi-circular arch, while the wide entrance for the hose cart had a Tudor arch. Tudor arches were often placed on government buildings such as firehouses and armories during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Colorado.

Utilities. The city water system established in 1882 included a brick pump house with a stone foundation, a cross-gabled roof, and hood moulds with Tudor arches over doors and windows (See Figure 30). In 1904 and subsequent years, the structure and the system were expanded and enlarged.

County Courthouse. The two-and-a-half-story Second Empire style brick courthouse (demolished) designed by Denver architect William Quayle was highlighted by a central three-story entrance tower with mansard roof and arched windows with stone hood moulds, oculus windows, and pediments (See Figure 31). The building featured a bracketed cornice, bays topped by pediments, and an elaborate entrance with classical details. The Fort Collins Redstone Company donated a red sandstone cornerstone from their local quarries for the building. Barney Des Jardines of Fort Collins was the contractor for the courthouse, which cost $39,379. Kemoe & Bradley did the stone work and John G. Lunn subcontracted the brick work on the building.

Churches. The Gothic Revival was a popular style for churches long after it had fallen out of favor for residential buildings. Gothic churches employed such features as pointed or Gothic arch windows, towers, flying buttresses, and recessed entrances. St. Luke's Episcopal Church (demolished) was a small, 1882 Gothic Revival chapel with steeply pitched gabled roof, gabled entrance bay with double doors with pointed arched opening, pointed arched windows, and flying buttresses.

St. Joseph's Catholic Church at 300 West Mountain was constructed in 1900, with stone from the quarries west of Fort Collins, including the Stout quarry, the Frye quarry, and the Lamb quarry. Lamb donated one hundred tons of stone for the church. The stone utilized in construction was buff and gray sandstone which was transported by train and wagon to the building site. The church had a steeply pitched central gable flanked by a tall entrance tower with belfry and a short secondary entrance tower with arcaded upper story, all with numerous pointed arched openings (See Figure 32).

Gothic Revival churches also included a Christian Church (demolished) at the corner of Magnolia Street and College Avenue, a brick building with steeply pitched gabled roof and a square entrance bay with cross gabled roof and pointed arch entrance with stained glass and double wood paneled doors. The building had decorative brickwork, a raised, rusticated stone foundation, and evenly spaced pointed arch windows. The 1904 German Congregational Church at the corner of Whedbee and Oak was a Gothic Revival building with cross-gabled roof and a large, square entrance tower with pinnacle, pointed arch louvered vents, and arched entrance. The building had massive stained glass windows with Gothic arches and a raised stone foundation. The 1903 Baptist Church (328 Remington) was a fortress-like structure, with rusticated stone walls, and a large, square entrance tower with crenelated roof. The church had large stained glass windows with Gothic arches and a tall spire.

Commercial Buildings. As the town gained in prosperity, the false fronts were replaced by architecture developed in the East and transferred to the western towns via trained builders and architects. The arrival of the railroad made a variety of building elements available at reasonable costs and mass produced ornaments allowed buildings to achieve individual distinction formerly possible only for the most expensive edifices. Many of the more sophisticated buildings reflected elements of the Italianate, Queen Anne, and Romanesque styles.

Italianate style commercial buildings were of two to three stories, with flat roofs with ornamented cornices and elaborately detailed windows. The buildings were divided into long, narrow shop spaces on the main level, with a central, inset entrance. Double shopfronts had two entrances, either in the center of the building, or separated and flanked by display windows. To make blocks larger, the same storefront form was repeated several times on one building facade under a single cornice. Italianate details on a commercial building could include such features as second story oriel windows, bracketed cornices, and quoins at building corners.

Cast iron fronts, which were invented in New York in 1848, rapidly became popular for nineteenth century commercial structures in Colorado, including Italianate style buildings. Cast iron fronts, which could be ordered in catalogs, were viewed as durable, economical, fire resistant, and easily reassembled. Several cast iron manufacturers were located within the state. As Eric Stoehr has noted, "the facades could be prepared and fitted in the factory, transported to the site, and put together rapidly in all seasons of the year. They were deliberately made to look like the already accepted wood and stone fronts." Metal was also used for window detailing, and elaborate cornices. A plaque proudly identifying the builder of the cast iron front was often found at its base.

In an exuberance of ornamentation to match the Queen Anne style of residential construction, shop owners could choose from multiple construction materials, cast iron facades, molded or carved window surrounds, decorative cornices, elaborate panels with the owner's name and building date, and richly detailed entrances. Paneled doors with leaded glass and decoratively molded door handles, patterned iron footplates, brass hardware, and tile floors all spoke to the prosperity of the businessman and the luxuries to be found within the establishment.

Less elaborate buildings of the late nineteenth century were distinguished by their brickwork. The one or two-story buildings were characterized by decorative Queen Anne brick corbelling along the cornice line. These buildings usually had flat roofs, and first floor storefronts with living quarters or offices above. The storefronts featured large display windows, clerestories, paneled kickplates, and recessed entrances. Decorative brickwork was evidenced not only at cornice level, but could also be found in window lintels and sills, belt courses, and corner beveling.

The Romanesque Revival style began as a historical revival of Medieval church architecture. American architect Henry Hobson Richardson's interpretation of the style was new and innovative, creating an American version known as Richardsonian Romanesque. As a residential style, it first appeared in the 1870s and reached its height of popularity in the 1890s. The Romanesque style was not considered a poor man's style and was intended for large, freestanding buildings. The composition required the work of skilled designers and experienced craftsmen. The design was intended to reflect substance, prosperity, and how the wealthy felt about themselves as reflected in the "home as castle" concept. The style was considered urban rather than rural and was found only in the most prosperous towns, mostly in the Northeast and Midwest. Richardsonian Romanesque is characterized by the semi-circular arch, which was often combined with square towers of varied height, heavy, rusticated stone construction, round arches, contrasting colors, and short towers.

Hotels. As the town matured, hotels became more lavish and were decorated with Italianate, Queen Anne, or Second Empire detailing. The three-story brick Tedmon House (demolished) built in 1880 had a cornice of decorative brickwork and a slightly projecting, central, pedimented entrance. A corner entrance of the building led to the City Drug Store. Above the corner drug store entrance were second and third story squared bay windows. The evenly spaced windows of the building had flat arches with heavy stone lintels on the first and second story and segmental brick arches with stone tabs on the third story.

The 1883 Loomis Block, which housed the Linden Hotel, was a three-story Italianate commercial building featuring a corner tower with corner entrance and bay windows on the second and third stories, topped by a pyramidal tower roof (See Figure 33). The corner entrance with second and third story bay windows made the building reminiscent of the Tedmon House, and was a popular design element for prominent commercial buildings of the period. However, the Linden Hotel had a heavy bracketed metal cornice. Windows of the building varied in design from floor to floor, with the first having tall, segmental arched windows; the second story having round arched windows; and the third having flat arched windows. Each group of windows had decorative crowns and sills which were connected to form courses.